Community Peace and Justice - from a Faith Perspective

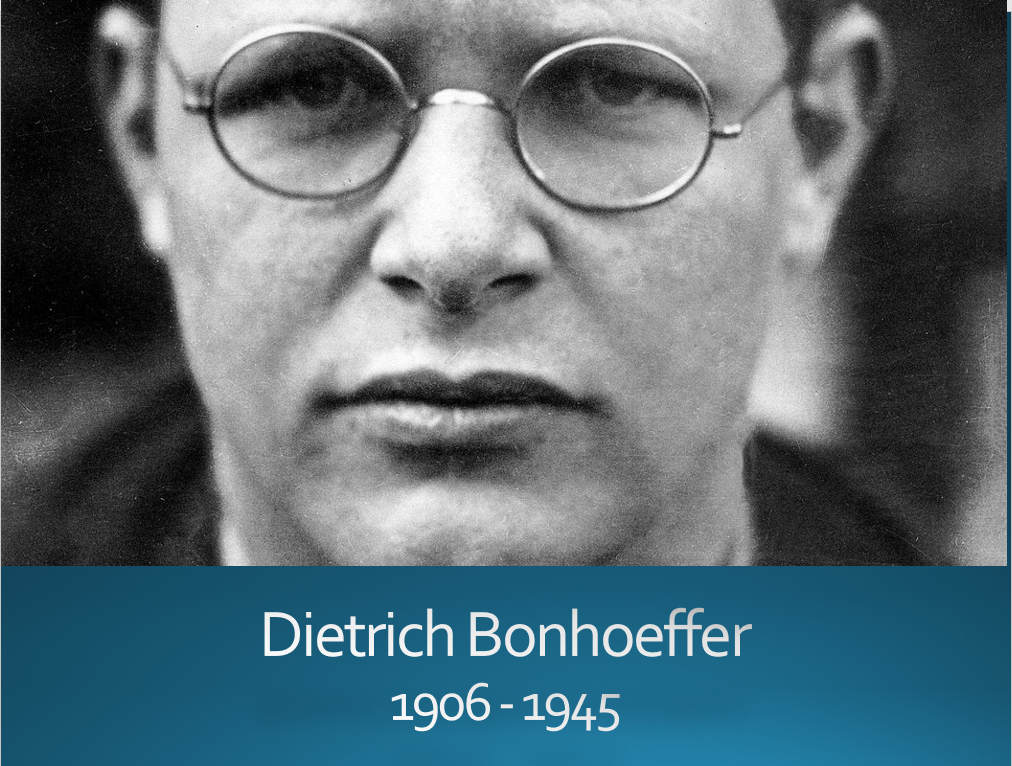

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Resources – Reading

(click on blue links on left)

“That he came from the upper classes no doubt played a role, but surely what Muller and Schoenherr identify as his “grounding the concrete community in the reality and activity of Christ” was crucial if we are to understand his early opposition to the Nazis.

The question for us is how that “grounding” might help us know better the challenges before us. I suspect it is a mistake – and a quite understandable one – to assume that what you are against is sufficient to define your moral identity, rather than what you are for.”

Reflection on the often asked question today: “Is this a Bonhoeffer Moment?” on BaptistNews.com, October 2017

“Bonhoeffer’s insights are worth revisiting when we feel “no ground under our feet,” a situation he describes in an essay written early in his imprisonment, now the first chapter of his Letters and Papers from Prison.”

Bill Leonard is the James and Marilyn Dunn Professor of Baptist Studies and professor of church history at Wake Forest University School of Divinity.

“It has become abundantly clear that [the Churches’] failure to respond to the horrid events…was not due to ignorance; they knew what was happening. Ultimately, the Churches’ lapses during the Nazi era were lapses of vision and determination.”

The German Churches and the Nazi State – Victoria Barnett

“How did Christians and their churches in Germany respond to the Nazi regime and its laws, particularly to the persecution of the Jews? The racialized anti-Jewish Nazi ideology converged with antisemitism that was historically widespread throughout Europe at the time and had deep roots in Christian history. For all too many Christians, traditional interpretations of religious scriptures seemed to support these prejudices.”

While the article is long, it offers helpful historical context.

What must be clear, however, from the detailed analysis of Schlingensiepen’s account of Bonhoeffer’s relationships, his participation in the German church struggle, his unconventional formation, and his radical theological ideas, is that Bonhoeffer is exceedingly complex. No biographer will portray him faithfully without a great deal of historical and theological spade work. Schlingensiepen focuses on Bonhoeffer’s intellectual curiosity, strong moral compass, courage, and creative modern theology. I have suggested that these characteristics make Bonhoeffer unpredictable, paradoxical, and impossible to pigeonhole. Conservatives value a Bonhoeffer who teaches the Bible, stands upon confessions of faith, and takes the lordship of Christ so seriously that he is willing to kill or die for it. He is, to be sure, a serious Christian. Liberals value a Bonhoeffer committed to peace, internationalism, and ecumenical Christianity—a cultured and curious man open to literature, music, and modern life, including an intellectually critical relationship with both the Bible and confessional theology. In Schlingensiepen’s biography of Bonhoeffer, we discover a man who encompasses both of these images and somehow holds them together in a life marked by a most radical, subjective, and challenging form of Christian discipleship. Here is someone worth knowing.

“Martin Luther is such a towering figure in German history that it’s no surprise Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich exploited his name whenever it could.

Most visitors to events in Germany marking this year’s 500th anniversary of the Reformation, however, probably didn’t expect to find an exhibition setting out just how extensively the Nazis used Luther to justify their anti-Semitism and nationalism.” . . .

. . . The Nazis marked the 450th anniversary of Luther’s birthday in November 1933 with a nationwide “German Luther Day,” in which the main speaker praised Luther’s “ethno-nationalist mission” and called for “the completion of the German Reformation in the Third Reich.”